Freemium and free-trial signups have one thing in common: Neither generates revenue.

You may agonize over the decision to choose one path over the other, but you can save that strategic energy for figuring out how to transition more free users into paying customers.

This post details the freemium and free-trial models and considers the key questions—about your business, your market, and your product—that guide you toward the best option.

What both strategies are—and are not

Neither freemium nor free trial will rescue an ailing SaaS company. If your onboarding experience is terrible or your product uninspiring, you’re wasting time with the “freemium vs. free trial” debate.

A freemium or free-trial approach impacts the micro-conversion of an unpaid product sign-up. And optimizing for micro-conversions can undermine macro-conversions, especially if your marketing team never sees what happens after a form fill.

So what should you do first? Define your go-to-market strategy. As Wes Bush details, you have three options for a SaaS go-to-market strategy: sales led, marketing led, or product led. Both freemium and free-trial programs are product-led strategies: they show instead of telling.

If you haven’t committed to a product-led strategy, you can stop reading now. But if you’ve already started down the product-led path—and can get it right—there are plenty of benefits.

Why product-led strategies work for SaaS companies

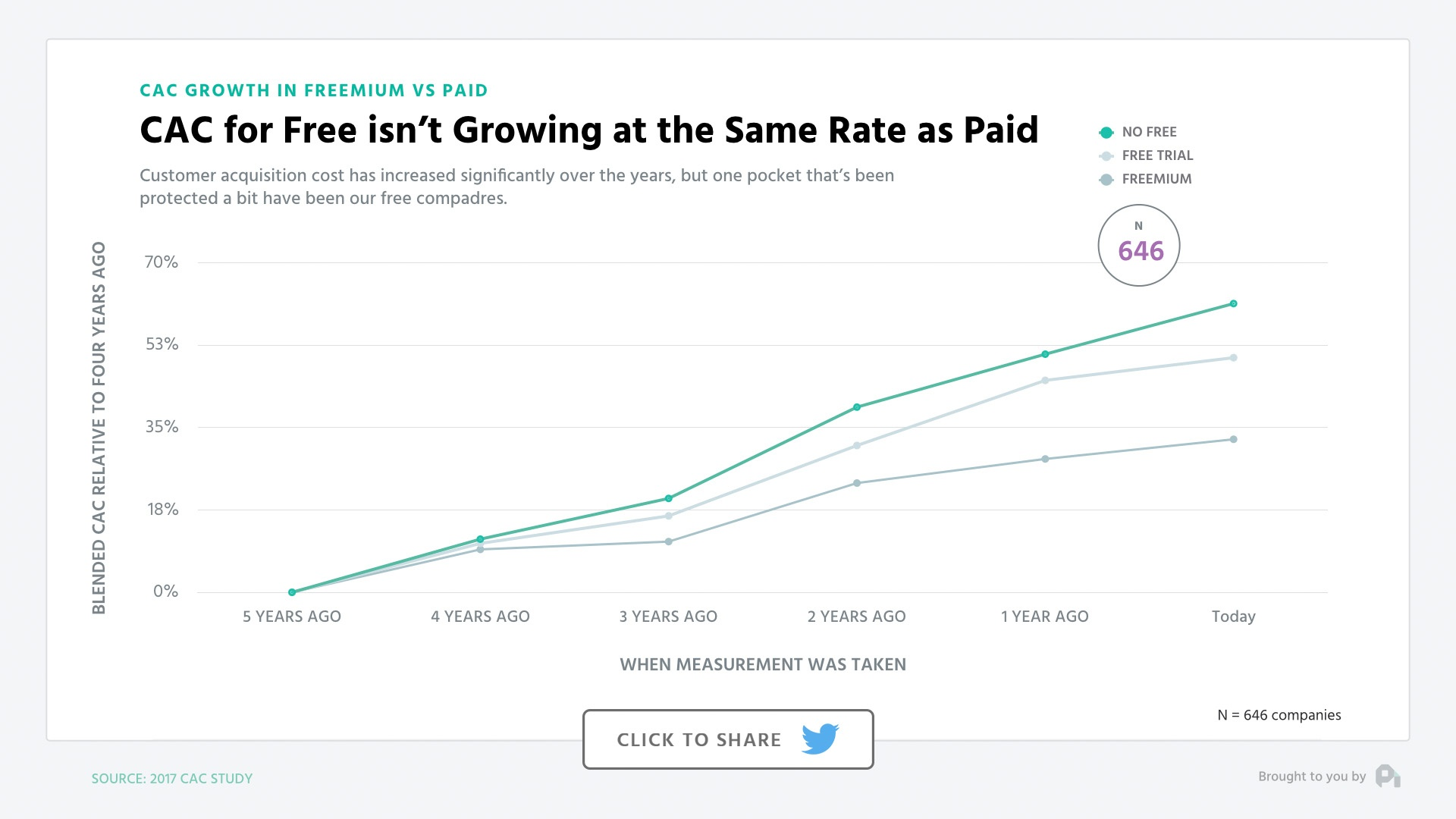

Freemium and free-trial strategies can reduce customer action costs (CACs). Research from ProfitWell shows that both have lower CACs compared to no product-led option—with the gap continuing to grow:

Even with a product-led strategy:

- Will you still spend marketing dollars to get users to sign up for freemium or free-trial versions? Yes.

- Will you still need sales support for some enterprise accounts? Probably.

But rather than spending marketing dollars on expensive, bottom-of-funnel ad buys—or on content that attempts to explain the value of a product—a product-led strategy lets consumers create their own “Aha!” moment. And if you’re not spending money persuading those users with ads or whitepapers, you can pour those resources back into product development.

Consumer psychology also suggests why product-led strategies may enjoy more success:

- Endowment effect. We value things more highly if we own them. Freemium or free-trial access increases a sense of ownership and, therefore, may increase its perceived value.

- Mere-exposure effect. If we’re more familiar with a product (person, or anything else), we’re more likely to have positive feelings for it.

- Loss aversion. We fear loss. A pending end to a free trial can encourage a purchase. With freemium, it’s relevant only if a company bumps up against a freemium limit and must upgrade to premium or migrate to another product.

Despite the benefits, getting unpaid users to become paid users—”crossing the penny gap”—is hard.

The formidable penny gap

Scaling from $5 to $50 million is not the toughest part of a new venture—it’s getting your users to pay you anything at all. The biggest gap in any venture is that between a service that is free and one that costs a penny.

– Josh Kopelman, First Round Capital

The penny gap is the transition point from unpaid to paid customer, and both freemium and free-trial options must convince users to cross it. The gap is even wider for freemium offerings: At the onset of the relationship, user expectations are that the product is free.

To dispel this perception, Sixteen Ventures’ Lincoln Murphy emphasizes the need to immediately and repeatedly remind users that they’re accessing the freemium version of a premium product.

So, realistically, how many of those freemium and free-trial users can you expect to convert?

Benchmark conversion rates: freemium vs. free trial

Benchmarks have limited value: A “good” conversion rate is one that’s improving. Still, which product-led strategy—on average—converts better: freemium or free trial?

As Ada Chen Rekhi details, free trials usually convert at a higher rate, but rates vary widely:

- Freemium. Lincoln Murphy cites a 3% conversion rate for SaaS and B2B web apps; a 2012 article on several leading platforms suggested a range between 1 and 10%. Slack, in 2014, converted at 30%.

- Free trial. A much-cited but dated Totango study pegged the conversion rate (for opt-in free trials) at 15% for SaaS businesses; the rate jumped to 50% for opt-out trials. Single-company reports in 2016 from Chargebee, Justuno, and Recapture.io ranged from 10 to 25%.

The spread of conversion rates stems, in part, from the myriad ways you can deploy a freemium or free-trial strategy.

Freemium, free-trial, and hybrid models

Murphy argues that the choice is not between freemium and free-trial strategies but between freemium and premium products. (The latter may include a free trial.) Why the distinction? Because a freemium version is an independent, forever-free product that requires a conversion strategy.

Too often, SaaS companies roll out freemium strategies under the assumption that freemium users naturally cross the penny gap to become paying customers. In reality, freemium users are often an unmonetized segment that helps top-of-funnel marketers hit their numbers—but little else.

It’s one of many critical distinctions. These are the others:

Freemium models

A freemium strategy offers perpetual access to a restricted version of a product. Restrictions come in many forms:

- Feature limitations. This is the most common form of a freemium product—a no-frills version of its premium counterpart (e.g. Evernote).

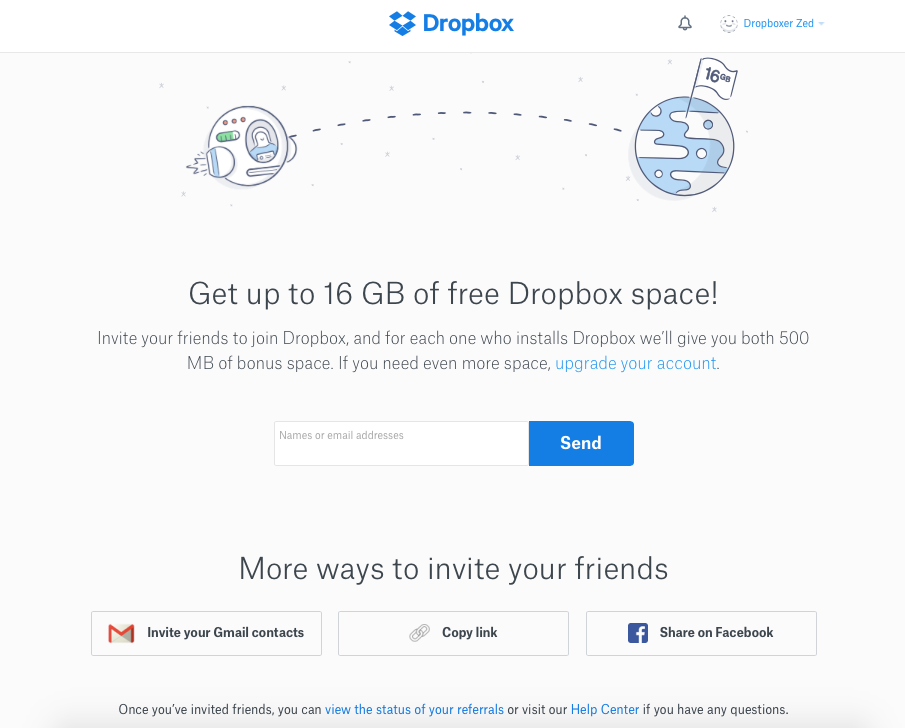

- Usage limitations. The freemium version limits storage or server access (e.g. Dropbox), or caps the number of users (Canva).

- Advertisement additions. Not every restriction removes functionality. Freemium versions can also include advertisements as a limitation on the experience (e.g. Spotify).

- Cross-sells. Some freemium products are fully functional (e.g. iTunes), but access to them is an entry point to an ecosystem that incentivizes future purchases (e.g. iCloud).

Other products are fully free (e.g. Instagram) with other means of monetization, like advertising. While not freemium products—there’s no paid version to which you can upgrade—they represent one end of the free vs. paid spectrum.

If freemium still seems like a barrier to acquisition, you’ve got plenty of money in the bank, and you’re crossing your fingers for a buyout by Google or Facebook, a fully free product may make the most sense.

Free-trial models

A free trial gives users full access to a product for a limited period of time.

In an interview with HubSpot’s Kieran Flanagan, Ty Magnin of Appcues suggests that a free trial is the “demo of 2018.” That’s because most SaaS products are accessible immediately via a browser or app and automate onboarding: they’re self-paced, time-limited demos.

There are two ways to structure free trials:

- Opt-in. Users sign up for free without including any payment information. They can explore the product until their trial expires, at which point they’re prompted to sign up—pay or get out.

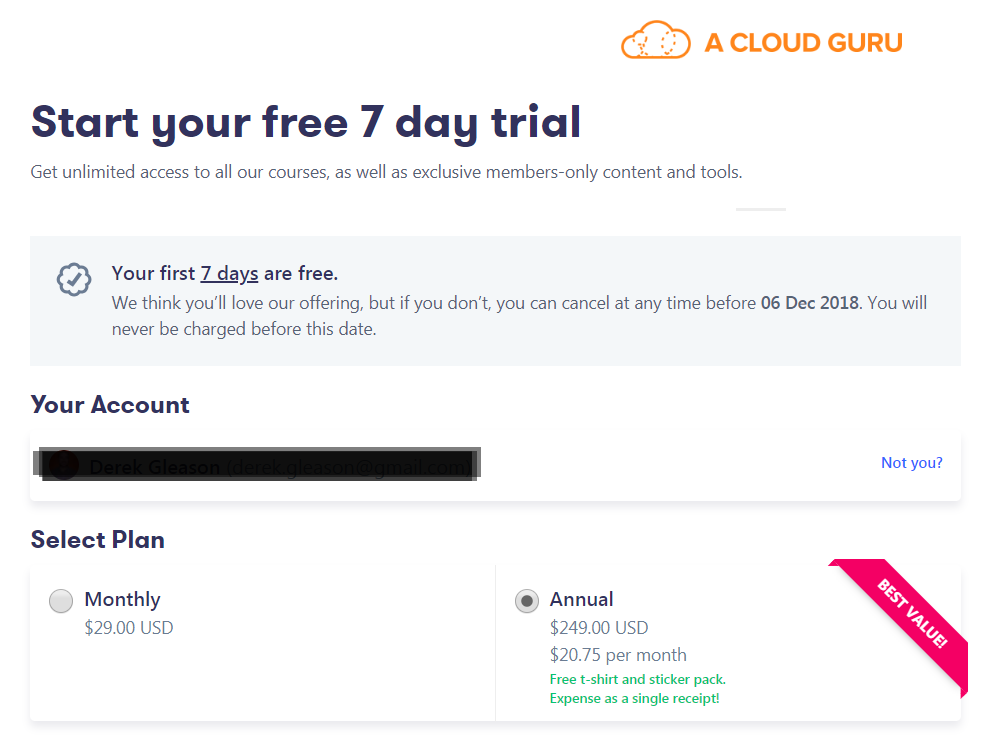

- Opt-out. Credit card information is taken at the start. At times, a nominal fee such as $1 is charged, often to placate payment processors or to cross the penny gap early on. If the user doesn’t cancel by the end of the trial, they’re billed automatically.

An opt-in free trial typically generates more trials because it reduces friction at signup; however, an opt-out free trial generates a higher percentage of sales (often of the “Gotcha!” variety), as some users forget to cancel in time. Those near-term sales, while enticing, may erode a brand and hurt retention.

Credit-card walls are also a tactic to keep out the “riff-raff,” an option Murphy cautions against:

a CC-wall doesn’t prevent abuse, it just lets fewer people in so you have less abuse [. . .] putting up a CC-wall doesn’t make a lot of sense most of the time; it is often used to cover up things that should be fixed or because you don’t believe that your Free Trial is setup to convert customers (which it probably isn’t).

In other words, a credit-card wall has consequences, not all of them desireable: It will keep out bad and good prospects, and it will tank your sign-up conversion rate (while likely skyrocketing your post-trial conversion rate—see the benchmarks above).

A Cloud Guru has enjoyed exceptionally high conversion rates for opt-out trials. Note that they clearly advise users of pending charges.

For some, opt-out free trials are essential—you may have more leads than you can manage or face rampant trial abuse. Nonetheless, sharpening targeting for user acquisition or offering a trial only to some users (e.g. those already on an email list) may reduce the need for an opt-out version (and sign-up friction for legitimate prospects).

Hybrid models

What should happen when a free trial expires? For SaaS companies with hybrid strategies, those users migrate back into a pool of freemium users:

If loss aversion isn’t enough to catalyze a purchase at the end of a free trial, a hybrid free trial–freemium strategy can keep those users in the funnel—assuming there’s a strategy to advance them through to purchase (or product advocacy).

Murphy highlights that concern in a similar user flow:

Well-known SaaS companies have succeeded with a hybrid model. (HubSpot offers free trials within freemium and paid versions of their products.) But how do you know which makes sense for you?

How to choose between freemium and free trial

As detailed below, the use cases for freemium are limited, and, if your company isn’t a fit, a free trial is the fall-back option.

Getting to that decision point comes down to answering questions about:

- Your business.

- Your market.

- Your product.

Questions to ask about your business

Who are you selling to?

Is it the same person who uses your product on a day-to-day basis? If not, a product-led strategy may not be right at all. (A sales-led strategy may work better.) On the other hand, a freemium strategy may work well with a bottom-up approach that requires time to scale.

Consider Slack: At a large organization, the eventual purchasing decision may come from the C-Suite (where it’s used sparingly, if at all), but the request for that purchase could develop over time as more and more departments within the company rely on it for communication.

The inertia that regular use builds—historical knowledge, platform familiarity, etc.—makes switching difficult. Reaching that level of inertia takes longer than the duration of a free trial.

Advocacy depends on widespread adoption, but users are not homogenous: Freemium accounting software may be simple to a college administrator but complex to an independent contractor. Ensure that “easy to use” applies to every target demographic.

What are your goals?

Companies like Spotify and Canva created massive user bases by giving away a high-value product. As Kieran Flanagan explains, however, each did so with different goals in mind:

- Market domination. For a product like Spotify, a freemium version drove rapid adoption that established the company as the dominant business in a crowded market.

- Market disruption. Canva isn’t trying to win a head-to-head competition with Adobe. However, its freemium version is good enough to create loyal users who would rather spend thousands on something other than Photoshop.

The danger, of course, is that both market goals optimize for more free users. Spotify and Canva didn’t become freemium success stories until they monetized their user bases.

And, like bottom-up efforts, both were a slow burn that required tens of millions in funding to sustain the glut of free users that precedes revenue. To generate that financial support, a SaaS product needs mass appeal.

It’s why your market may be the best guide to choosing a freemium or free-trial strategy.

Questions to ask about your market

How big is your market?

If you ask Jason Lemkin of SaaStr, he’ll tell you that you need 50 million active users to make freemium work. (By “work,” he means building a $100 million business.) That’s why most freemium success stories feature products that appeal to most people.

Not everyone is hoping for an IPO, however, which means that freemium is possible in smaller markets if the conversion rate is higher and the revenue per paid user also rises. (Lemkin’s back-of-the-napkin math assumes $10 per month per paid user.)

As Vineet Kumar argues in the Harvard Business Review, it may be easier to identify the right model by targeting a conversion rate. Kumar suggests that a 2–5% conversion rate is a reasonable balance; the more niche the market, the higher you should peg your target conversion rate.

So, if your conversion rate is 35%, you may want to consider a freemium option to expand your market. However, if your conversion rate is less than 1%, you may want to restrict access.

The size of your market isn’t the only consideration.

How mature is your market?

What product are you displacing? Murphy believes the answer is key to identifying the right customer-acquisition strategy.

For B2B SaaS products, the added challenge is that the choice for consumers is often all or nothing: Companies have one CRM, one email marketing platform, one CMS, etc. That’s different from B2C SaaS products (Murphy uses the example of smartphone games), in which consumers may simultaneously use several.

Regarding displacement, there are three potential answers:

1. You’re displacing a popular commercial product. You’re entering a product category with wide adoption for which people expect to pay money—two key benefits. But it may also be the hardest market to break into; you’re a disruptor. A freemium approach, like Canva’s, may motivate users to try an alternative solution.

2. You’re displacing an archaic system. Does your SaaS product achieve something that a patchwork of spreadsheets currently does? Your product may offer a ton of value, but you’re also asking people to pay for something they currently get for free. (Or, at least, the cost of the existing solution is buried in extra hours of labor.)

Is a free trial enough time for users to establish a new habit? Or will it take the promise of a forever-free product to convince them to migrate a process to your product? If you think a freemium version is necessary to inspire a shift, beware that you’re replacing one free product with another. At some point, you’ll need to convince users to pay.

3. You’re displacing nothing at all. Are you offering a never-before-imagined SaaS product? Freemium could expedite adoption and dominance. After all, you have no competition—yet.

However, you also establish the expectation that your new service is free. A free trial may let you figure out quickly—and, perhaps, painfully—that there’s no market at all.

What is the network effect in your market?

Freemium’s core growth engine is social proof aka word-of-mouth marketing. To drive word of mouth marketing, a freemium business needs a community, typically an existing one which falls in love with the business’s product.

Freemium requires an active, engaged market with a strong referral network to monetize (albeit indirectly) legions of non-paying users. Freemium products expect that a majority of users will never become paying customers; however, those freeloaders pay for their use by spreading awareness.

The network effect is stronger with freemium products—users share something of permanent value.

For generating word-of-mouth referrals, freemium beats free trial: Freemium is a product, not a sample, and, as a result, is worth sharing. Still, that sharing won’t occur organically. As Murphy emphasizes, freemium products must catalyze the network effect (e.g. Dropbox lets you give free storage to your friends.)

Identifying those trigger points—to entice new users and convert them into paying customers—requires deep product knowledge.

Questions to ask about your product

How expensive is your product?

An expensive product, according to Bush, doesn’t work with an opt-out free trial. (Bush argues against opt-out free trials in general.) For one, opt-out “free” trials often create a low initial anchor, like the nominal $1 fee, which makes the full price seem that much higher (to say nothing of the negative impact that even a one-penny price has on conversion rates—free is a powerful word).

Second, they yield unintentional purchases and, with a high price point, ones that may max out a credit card and infuriate users.

A $1 trial may create an anchor that makes a high-cost sale more difficult.

A freemium approach for an expensive product faces a similar risk: The penny gap grows wider, and freemium can devalue a high-end brand.

An opt-in free trial solves the aforementioned issues for expensive products. For inexpensive products, the decision point between freemium and free trial likely resides elsewhere.

Is your product easy to use?

No freemium offering comes without costs, even if those costs are a few GBs of server space. To ensure that onboarding and customer service costs remain low, however, freemium requires simple onboarding and total (or near total) self-service. (Bush offers another possibility: charging for user onboarding or folding those costs into the product’s price.)

As noted earlier, a diverse user base may make product onboarding suprisingly complex. And, of course, if users don’t understand how to use a product, they’re unlikely to become passionate advocates.

The same is true for free trials: The more involved the onboarding process, the greater the need for user qualification (unless you have resources to devote to added customer support).

How much do you know about your product?

Free trials use urgency to motivate a purchase. When trying to convert more free-trial users, you can test trial length—say, 14 days versus 30—but the variables are limited.

With freemium products, the variables are endless. Flanagan details the key questions:

[W]hat are the parts that are valuable enough that will help them spread the good word about how great that product is? And what are the features and things that they’ll need so much that they’re just going to pay you money?

If you want to learn which features users care about, freemium opens the floodgates. Freemium can serve, in effect, as a means to scale user research. You can rapidly test the addition or subtraction of features (to statistical significance) to determine which are stickiest.

At the same time, you may not have the patience (or funding) to endure an influx of new users. Piloting the software with a handful of companies may provide similar information at a fraction of the cost.

Ultimately, that data has value only when it connects to a user decision to upgrade. If you don’t know which features generate a sale—or, as The New York Times learned, exactly how many articles they should let you read for free (the answer was 10, not 20)—you won’t monetize those users effectively.

Of course, if your market is so small that you’ll never gather enough data, there’s no point opening the floodgates to begin with—a free trial ensures every user gets access to the most influential features.

Conclusion

Bush is fond of quoting Rob Walling: “Freemium is like a Samurai sword: unless you’re a master at using it, you can cut your arm off.” The default recommendation—from Bush, Walling, and others—is for an opt-in free trial.

That said, if your current conversion rate is high, a freemium option (or less-restricted free trial) may bring more users into the funnel and generate word-of-mouth to expand awareness.

In contrast, if you’re burning through cash trying to onboard hundreds of no-pay tire-kickers (of the freemium or free-trial variety), you should tighten the spigot.

And yet, in the end, the critical consideration is the execution of either strategy—rather than the choice of it—which has a far greater influence on how many evaluators become purchasers.