Stroll into your local supermarket and images of mascots assault the eyes from every direction. Cereal boxes, battery packs, dog treats and even salt sport mascots. But they don’t just exist to look pretty; these familiar faces are present for a very good reason.

The first mascots were ancient French charms designed to bring luck to a home. Today’s icons have a similar purpose, but they aim to boost profits for businesses. Whether it’s a sports team, a food item, or an insurance firm, brands carefully create the image of their product or service to ensure it sells.

But what makes a mascot successful? What should he/she/it convey about the company? There’s much to consider.

Real vs. Make-Believe:

The first deliberation any company should have is whether the mascot is a fictional character or a human spokesman. The two choices have unique pros and cons and will serve different businesses in different ways.

An illustrated, animated, or fictional character can be created for nearly any purpose, making it very versatile. Cartoon mascots can be designed in ways that real people cannot be. Products aimed at children often gain from this cartoon appeal. Kids enjoy watching animated shows and playing with action figures and Barbie dolls. They are attracted to the bright, friendly faces of cartoon characters. A study by healthfinder.gov in 2010 found that products with well-known cartoon characters on the packaging were more likely to catch children’s attention (not surprisingly), and in some cases, kids even said these products tasted better.

Another advantage to fabricated mascots is that while concept artists and animators will require contractual payment, the mascot itself will not be on payroll or receive royalties as a real person would.

Celebrities and otherwise human spokespersons also come with their veritable advantages. The masses are pre-loaded with views on certain celebrities, so adopting one for a spokesperson is instant publicity and attention from the public. Of course, strategically choosing someone based on the target audience is vital. For example, Lindsay Lohan would not be a wise choice for someone selling medication or insurance to people. If a company is going to successfully appeal to its target market, the spokesperson needs to emulate the given demographic’s values.

Another advantage is that real people can relate to real people, and therefore confide in them. Insurance firm Allstate does a remarkable job establishing trust and reassurance with their customer base through the earnest face of actor Dennis Haysbert.

But there are nasty risks that come with entrusting a business with one person’s image. Spokesmen (especially celebrities) can make mistakes, such as but not limited to drug abuse, driving under the influence, involvement in underground dog fighting rings, smacking prostitutes and other general debauchery. Let’s not forget about the likes of the beloved Charlie Sheen and Offer “Vince” Shlomi.

The bad juju following a spokesperson scandal can have unfortunate lasting effects. In Hanes’ case with Sheen, they fired him promptly. However, pre-meditated print ads were already scheduled to run months later and could not be pulled due to tight production schedules and contracts. Companies can learn a thing or two from these circumstances, as it’s imperative to preemptively anticipate celebrity screw-ups and have a plan B ready to go.

Aesthetic:

The mascot needs to convey an aesthetic that appeals to the target demographic. The type of service offered or product being sold should elicit the appropriate direction to go with mascot appearance.

Consider the colors used. Many companies make the choice of matching their mascot’s colors with the logo they use. This helps to keep branding consistent and builds immediate associations between the character and company logo.

Some businesses will go a step further and integrate the mascot’s likeness straight into their logos (such as Chiquita has done above, and insurance provider AFLAC), making the visual correlation even more poignant.

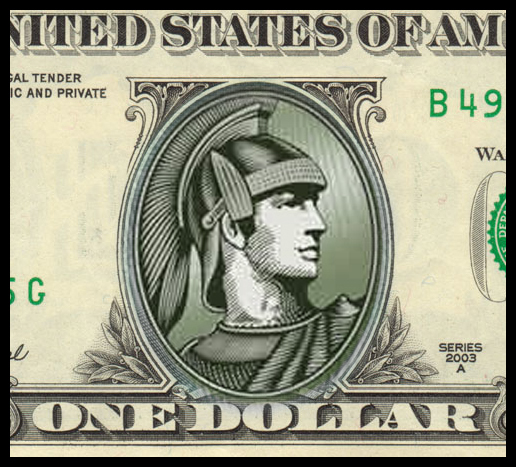

Color choice also has an impact on consumer reaction. The psychology behind color-driven marketing is powerful and widely recognized. Consumers link certain color schemes to distinct product niches. Many financial enterprises utilize light greens and blues because people think “money” and “credit.” American Express’s gladiator figure is perhaps the most literal example of this, and looks as if he could even stand in for Washington in a pinch. Hmm…

… and case closed. Presenting the consumer with a semblance that they’re intrinsically familiar with is also a solid way to captivate their attention, and to get them well acquainted with a brand.

Color even plays a part in triggering involuntary human reactions. Certain shades and combinations of brown, yellow, red and orange have been found to stimulate appetite. McDonalds’ pied spokesman Ronald McDonald is covered in stripes of ketchup-red and mustard-yellow for good reason.

Besides color, a mascot can take on a look that lends itself to a particular demographic.

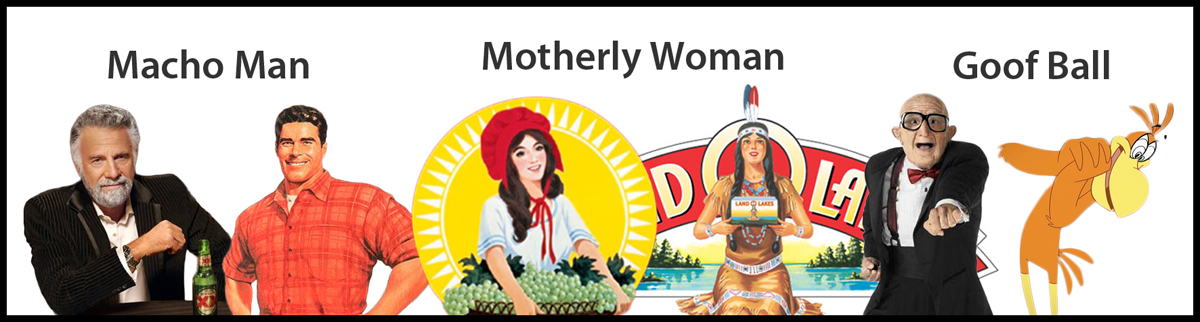

It’s not hard to tell that cliché get-ups will speak volumes about a brand and attract a certain customer demographic. Manly men take care of tough physical tasks (Brawny Lumberjack, Mr. Clean) and legitimize product interests for other men (but sometimes to little or no avail, i.e. “Alphanail” nail polish for men).

The stereotypical pleasant housewife is another frequented mascot aesthetic. Everyone knows the sweet nostalgia of their mother’s soft and caring aura, and brands will take full advantage of this. Food and baking products have been utilizing this approach with their mascots for over a century. Similarly, entertainment and breakfast cereal companies have come to understand the humorous drive behind the goofball façade. Kids will always be able to relate to the wild and crazy shenanigans of a cartoon rascal or dancing old timer.

Personality:

Any mascot’s demeanor should coincide with his looks. Is he energetic or laid back? Trustworthy and responsible, or mischievous and maniacal? Colorful or dry? It all depends on the target audience.

Let’s take a look at some well-executed examples of memorable mascot personalities.

The Dos Equis “most interesting man in the world” is portrayed as a cultured, suave renaissance man who knows what is the very best in taste when it comes to his product’s market. A splash of extravagant humor makes his pitch appeal to blithe beer drinkers and the masculine masses.

Aflac uses an obnoxious duck originally voiced by Gilbert Gottfried. The acronym’s resemblance to a duck’s quack gave the company direction, and its mascot is now one of the most well known in America. The clumsy waterfowl is featured in commercials spouting grating, unheard incantations of the company’s name to unsuspecting passers-by. Moral of the story: It’s hard not to remember a name after it’s squawked in your ear five times in thirty seconds.

Clear Eyes spokesman Ben Stein takes a more laid back approach. His dry disposition and matter-of-fact rhetoric has the same effect that the Aflac commercials do, but they accomplish the results differently. The drawling Clear Eyes “woooooowww” that Stein coined sticks in viewers’ heads and aids in brand recognition.

Occasionally a company mascot is an antagonist. Mucinex has created a prevalent brand through commercials featuring a mucus villain being vanquished by the power of their medicine. This gives mucus an extra bad rap through a vividly slimy character who grosses consumers out. His devious congestion schemes are carried out through an air of crude, rude, hillbilly-like swagger. Sometimes an effective way to sell a product is by contrasting it against an unfortunate reality, and this tends to work well for medicinal and insurance companies.

Wiggle room for re-branding:

It’s important to have a plan for when the shit hits the fan. Smart companies will be prepared to recover from a mascot mishap before the PR hell ensues.

As I mentioned earlier, the most common case of this happening involves celebrity irresponsibility. Aflac’s former duck voice actor Gilbert Gottfried was terminated after making several objectionable jokes on Twitter following the tsunami of March 2011. The company was wise to move quickly, setting a zero-tolerance precedent for misbehavior and bouncing back with an open call for auditions over social media.

Aflac effectively protected its hard-earned reputation by skipping the debate and jumping straight to replacement. Another problem with human spokespeople is that they will eventually kick the bucket, at which time a company needs a backup plan to inaugurate a new individual.

Another situation that could reflect poorly on a brand is when an illustrated mascot offends somebody. This has happened a hundred times before, and I don’t doubt that it will continue to occur as ballsy advertisers keep pushing the envelope. Some racially insensitive highlights from the past include Aunt Jemima as a half-literate plantation mammy, Count Chocula sporting a Star of David, and the Cleveland Indians’ eccentric mascot. Any company who cares enough about their image is going to have several savvy editors checking over potential mascot aesthetics and copy. Possible negative connotations need to be discussed before mascot concepts go to print.

Valuable advice in closing

So mascots aren’t quite as simple as they seem, even if all they do is run around in circles and scream. If nothing else can be taken away from this post, then I can only hope this simple rule of thumb will aid any growing business in developing a mascot:

(view original post on Prime Social Marketing)