It’s rare that technological genius and marketing savvy come wrapped together in the same person. We witnessed it in spades with Steve Jobs and saw glimmerings of it back-in-the-day with Michael Dell. Yet few folks in all of history wove together the technological and marketing arts more  deftly than Thomas Edison.

deftly than Thomas Edison.

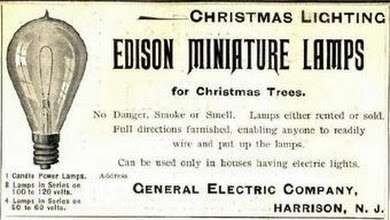

As we revel in glittering displays of holiday lights this season, we can hark back to the “tech and awe” the nation felt upon Edison’s first unveiling of twinkling Christmas lamps at his Menlo Park, New Jersey laboratory.

EDISON’S MARKETING SAVVY WOWED THE NATION WITH LIVE PHONOGRAPH DEMOS

A masterful showman, Edison’s marketing savvy created his first media home run in 1877 through live demonstrations of his revolutionary phonograph. The wonder of Edison’s “talking machine” literally stopped the presses at Scientific American on December 7 when the thirty year old geek brought his phonograph and tin foil record directly into the magazine editors’ office. He played a live demo record for them on the spot.

Astounded with the notion of capturing the human voice mechanically, the editors literally changed the December Scientific American edition to include an article on Edison’s extraordinary technological feat. Buzz from Edison’s derring do won him the opportunity to demonstrate the phonograph live both to Congress and to President Rutherford B. Hayes in April 1878—a veritable marketing bonanza. Thomas Edison’s name became known to every household in America.

MENLO PARK LIGHTING DEMONSTRATIONS

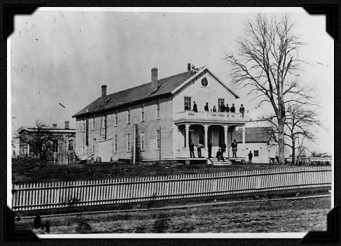

Some 18 months later, the Wizard of Menlo Park’s marketing savvy created a live demonstration of his latest innovation breakthrough—the light bulb—and the demonstration was key to winning public support. In a wild burst of enthusiasm, Edison elected to publicly display strings of incandescent lamps at his laboratory in the winter months of 1879, using numerous newspaper connections to get word out.

Talk about gutsy…it had been merely weeks since Edison’s October 1879 patent application for the electric light. He’d just masterminded the world’s first electric circuit, allowing him to connect light bulbs together and turn on an entire string of lamps simultaneously. Edison was also still working out bugs in the large electrical generators which powered his lighting networks.

In deciding to run a campaign for the wondrous light bulb via the press, Edison imagined drawing scores of people to Menlo Park to witness the thrill of seeing a landscape aglow on a winter night. In his zeal, Edison offered an interview several days before Christmas to a New York journalist from the Herald but made the journalist promise he would not spill the beans about his invention before the intended release date.

EDISON SCOOPED BY A JOURNALIST

Well…of course, after interviewing Mr. Edison, the journalist realized he had one of the greatest newspaper scoops of all time. Unable to contain his excitement, the journalist leaked his story for a handsome fee, which forced Edison’s hand on the timing of the public display. Rather than showing the lights in January 1880, the newspaper leak forced Edison to put up strings of lights on an accelerated schedule.

Here’s an account from Francis Upton, one of Edison’s most trusted lab employees, describing the frenzied situation in a letter to his father on Dec. 21, 1879:

Today has been quite exciting here since the morning’s Herald contained an account of the discovery of the lamp and the whole invention. Mr. Edison had allowed a Herald reporter to take full notes as to prepare his account for the exhibition which was to come off in a few weeks. The reporter was Edison’s friend and he thought he could keep a secret. Yet newspaper traditions were too strong and he sold out at a good price I suppose for he had the first full account.

Due to the leak, Edison had to fast forward his lighting display by several days. Frantic to complete adequate testing and to secure sufficient materials for several light strings, Edison and his teams rushed around to prepare for a public opening on Dec. 29. According to accounts, Edison reportedly looked “as if he had worked half his life out in searching for this electric light and was ready to sink into a premature grave.”

MARKETING SAVVY BRINGS THOUSANDS TO MENLO PARK

But even Edison at his most wide-eyed could not have anticipated the exuberant public response. Upon hearing of the great inventor’s plans to display electric lights at Menlo Park, exuberant crowds of celebrities, politicians, journalists, scientists, urban dwellers, and suburbanites flocked to New Jersey to see the illuminations with their own eyes.

On Monday, Dec. 29th of 1879, “the afternoon trains brought some visitors, but in the evening every train set down a couple of score at least…(T)he next evening the depot was over rum and the narrow plank road leading to the laboratory became alive with people…many hundreds have already come and hundreds more are coming…”

Managing crowds on the weekend was one thing, but Edison had not

On New Year’s Day the railroad ordered extra trains to be run and carriages came streaming from near and far. Surging crowds filled the laboratory, machine shop and private office of the scientist, and all work had to be practically suspended…

The volume of visitors was challenging not only for reasons of crowd control, but also the physics of weight-bearing in the laboratory area and viewing sites threatened the safety of the Menlo Park facility. “[T]he people came by hundreds in every train, and their combined weight more than once threatened to break down the timbers of the building.”

“Although Edison gave orders on 2 January to close the laboratory buildings to the general public and resume work, hundreds of visitors still came to see the illuminated windows and outside lamps.” Yet, Edison’s tour de force of technology was nearly thwarted multiple times by nefarious folk who intended a sullied outcome for Edison, aiming to short circuit the electrical system. Some even tried to tamper with Edison’s generators. Were it not for Edison’s watchful teams, these interlopers might have succeeded.

THE TECH AND AWE OF INNOVATION

Over 130 years since crowds first thronged to witness the electrical conjuring of the Wizard of Menlo Park, we are still drawn like fireflies to the “tech and awe” of innovation. Technological breakthroughs tap a universal chord of creativity within us all. And when these feats can be tethered to marketing genius, we rise just a bit closer to the heights achieved by Edison himself.

In bringing us decades of technological breakthroughs presented through his marketing savvy, Edison tapped the wonder we feel when the seemingly impossible becomes real. Today, the magnetic power of innovation still strikes awe in our hearts with every twinkling Christmas light.