Every business is focused on the bottom line: Making sure revenue exceeds costs each month. One big line item for most companies is spending hundreds–or, in some cases, even thousands–of dollars on acquiring new customers. Once you get that customer, what then?

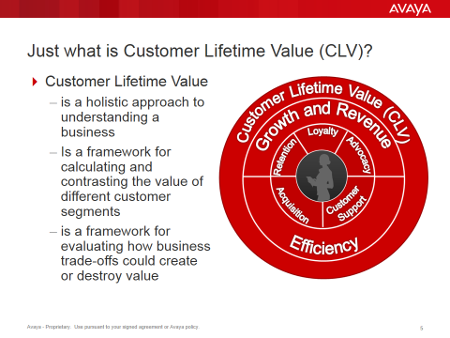

Customer Lifetime Value, or CLV, is a different way of looking at the customer equation. If your business isn’t measuring CLV, read on. Doing so could be the key to a healthier bottom line.

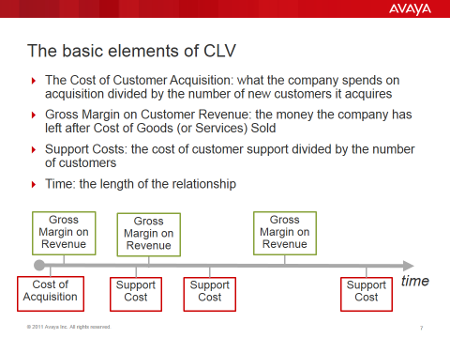

Your relationship with your customer likely didn’t happen by accident, did it? There was intent on the business end, and that is manifested in money spent. You need a customer, and your customer needs solutions. The “monkey in the middle,” as it were, is the cost of doing business.

No one likes the the cost of customer acquisition. In an ideal world, your product or service would “go viral” and you’d have people lined up around the block to just hear about it, but that’s something most people just dream of. Here’s the good news: customer retention can help balance out the costs spent on customer acquisition. It’s much less expensive to keep a customer than it is to court a new one.

By minimizing costs, you’re able to boost your gross margin on customer revenue. These elements provide the core of Customer Lifetime Value.

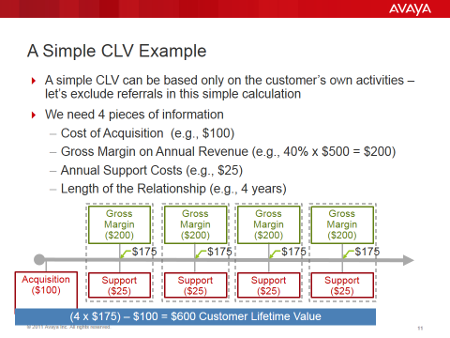

Let’s take a look a simple CLV example, based on the customer’s activities (excluding referrals, for clarity). We’ll peg the cost of acquisition at $100, the gross margin on annual revenue at $200, and annual support costs at $25. Let’s say the relationship is four years in length.

This gives us a CLV of $600, when you subtract the support cost from the gross margin of $200, multiplied by four years.

A quick aside: Customer referrals are always good to have. Word-of-mouth carries a great deal of weight, because there’s a certain vouchsafe that comes from more personal nature of the recommendation. Why else do you think Facebook was pushing social ads?

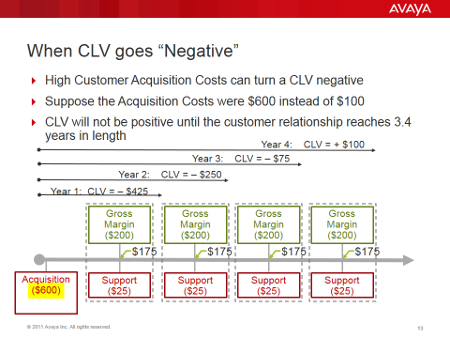

So what happens when a CLV goes “negative” (into the red)? Let’s suppose the acquisition cost is increased to $600, with the rest of the stats remaining the same. It would take three-and-a-half years for the business relationship to yield growth.

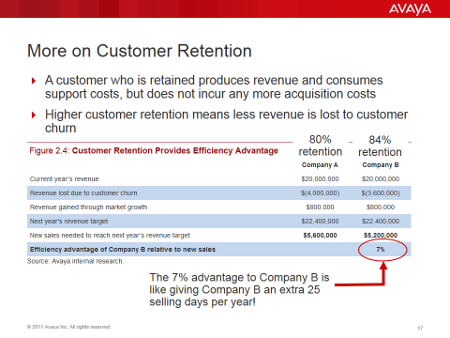

Let’s get back to customer retention. A customer who is retained produces revenue and consumes support costs, but does not incur any more acquisition costs. Higher customer retention means less revenue is lost to customer churn, and when the numbers are all worked out, equates to more selling days each year. Imagine if you magically had the equivalent of 25 extra selling days a year – When you look at the increased efficiency, the end result is very much like that. (If I was a retailer, I’d place those days between Thanksgiving and the end of the year in the United States).

So, how do you get started? Begin considering customer retention as the third lever of the business, joining the “revenue” and “cost” levers. As you get started, your CLV isn’t going to be perfect, but you can refine it over time and use it as a sounding board when you consider projects. If you are refining your customer segments or defining new customer “personas,” look at the CLV for each one as another way of informing yourself about each segment or persona – some segments might surprise you when viewed through the CLV framework.

It takes time to work out the kinks, but retaining customers for the long-term will yield serious growth for your business as you determine real Customer Lifetime Value.