Anyone in the working world knows this: Meetings are as hard to kill off as a supervillain in a James Bond film.

The move toward globalization and the reality of geographically separated teams is accelerating the move toward new forms of communication. Recent research has shown that this is beneficial for group task cohesion and performance (Shin & Song, 2011). Will emerging collaboration technologies continue to offer the same benefits? In this article, I’ll review the academic research on the impact of email, instant messaging (IM), and video on business collaboration, and suggest the good and bad things that the use of virtual avatars and social networking might bring.

Email: Convenient, But Limited

Cartwright and Kovacs (1995) identified three advantages to email: it is quick, it is convenient, and it is inexpensive. However, as email has proliferated, researchers have begun to note its disadvantages.

1) Email is no longer cheap. According to the Radicati Group (2007), employees received an average of 126 emails a day in 2006, up 55 percent from 2003. Employees were spending 26 percent of their time managing email. That was predicted to grow to 41 percent of their work day in 2009. This enormous increase in usage has elevated the cost of supporting email to $17 billion annually today.

2) Email wastes time. Jackson and colleagues (2003) found that employees are interrupted by email about every five minutes, hurting the productivity of both sender and receiver (Wilson, 2002).

3) Email is not good for urgent decisions. a sender doesn’t know if the receiver is available, nor if he or she will read the email in a timely manner (Luor, Wu, Lu & Tao, 2010).

4) Email is not rich. it is not real-time, lacks verbal and non-verbal cues, and conveys emotion badly (Cameron & Webster, 2005). The use of emoticons can help, though only if they are positive, as negative emoticons tend to be disruptive (Luor, Wu, Lu & Tao, 2010).

5) Email increases the number of “social loafers” and “free riders.” the former describes someone who reduces his/her own individual effort when working in a group with the assumption that others will make it up. the latter is an extreme example of a social loafer (Karau & Williams, 1993; Lantane and colleagues, 1979).

Here’s how it might work in real life. “Zestion” is a large Denver-based telecommunication company. Sophia, who is the marketing director of Zestion, recently initiated a process action team to better understand how customers use its products. the team included two members from the corporate office (Sophia and Oliver), two members from the Houston office (Juan and Theresa), and two members from the new York office (Theodore and Luciana). They have three weeks to complete their project and present it to management.

What happens if they use only email? Sophia and Oliver complete their portion and email their work to the other team members during the first week. Juan and Theresa “reply all” as soon as they get the email and indicate that they will be done with their portion soon. Juan and Theresa work hard to finish and send their work to everyone a couple days later.

However, neither Theodore nor Luciana respond. Theodore was sick and thought that Luciana had replied to Sophia, while Luciana was waiting for Theodore’s return to reply. After three days, Sophia emails asking if they had received her initial message. Luciana immediately becomes concerned that Sophia is angry at their lack of communication. she forwards the message to Theodore, who still doesn’t respond. Worried about the reaction from Sophia, Luciana decides to do all of the work herself. The result? Poor communication, hurt feelings, and a “free rider” (Theodore).

Although email use has been steadily declining among university students since 2005 (Judd, 2010), of email users will still grow from 2.1 billion in 2012 to 2.7 billion in 2016 (radicati). While antiquated to some, email clearly remains one of the most important ways that organizational members communicate.

Instant Messaging: Getting Closer

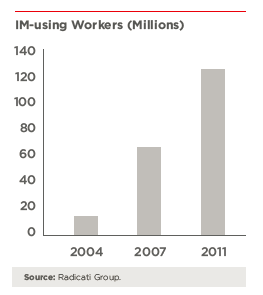

In 2007, more than 67 million people used IM at work, up from only 11 million in 2004 (Shiu & Lenhart, 2004). While data hasn’t been recently collected, Radicati (2007) estimated that over 120 million people would be using IM in the workplace by 2011.

IM has several advantages. It’s real-time. It’s richer than email. And it lets users easily switch to even richer mediums, such as voice or video over the internet (Anandarajan et al., 2010). IM users can also know the presence of the people with whom they are communicating. Finally, IM can be more cost-effective than telephone, email, and travel (Peslak, Ceccucci & Sendall, 2010).

What Are The Potential Downsides?

1) Privacy. Patil and Kobsa (2004, 2005) interviewed employees who use IM and found they were uneasy that their IM conversations IM-Using Workers (Millions) could be saved and forwarded to others. Those employees were also concerned that IM logs could be saved and retrieved at some future time, leading to problems with misinterpretations. some were even concerned that their “available” status could be used as evidence that they weren’t being productive.

2) Interruptions. Cameron and Webster (2005) found that over half of the people they interviewed indicated that IM interrupted their work. However, more recent research indicates that might be overstated. OU and Davison (2011) found that IM only accounted for 5 percent of workplace interruptions (others being telephone calls, email, face-to-face communication, and meetings).

3) Abandonment. Birnholtz (2010) studied 21 IM users who had adopted and then abandoned IM. They believed that IM left them too available (privacy) and that they were often interrupted by people with whom they did not want to talk, or had a hard time finishing IM conversations.

What might have happened if the Zestion team had used IM instead of (or in addition to) email? Sophia could IM the “available” team members with her and oliver’s portion of the work, and follow up by email with those that were unavailable. When Luciana receives the email, she sends an IM to Theodore letting him know about it. He sends a message back to Luciana letting her know that he is sick, but will try to be back to work in a few days. meanwhile, Luciana sends an IM to Juan and Theresa in Houston letting them know that Theodore is sick, but that she is working on their portion of the project.

But when Juan doesn’t answer her initial IM, Luciana sends several subsequent messages. Juan perceives this as pushy and domineering. Annoyed, he forwards a copy of the messages to Sophia as a record of what he considers “harassment” by Luciana. When Sophia tells Luciana, Luciana is angry at the violation of privacy. So what IM giveth, it also taketh away. newer technologies might assuage these problems.

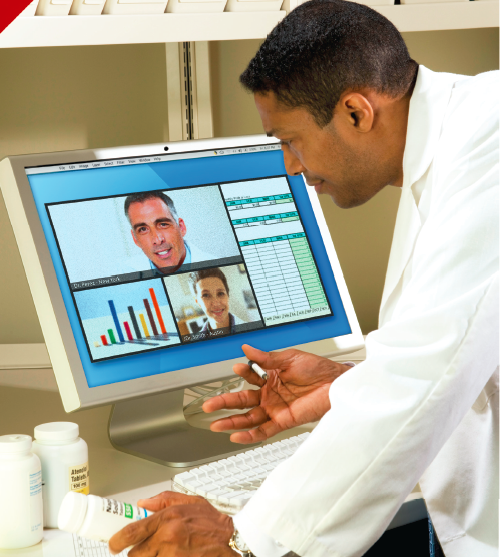

Videoconferencing: Richer and Richer

Much of the attention on videoconferencing has focused on its ability to decrease travel costs. But as collaboration among geographically separated team members requires audio and/or visual cues (Bekkering & Shim, 2006; Wegge, 2006), videoconferencing may be the primary tool to which organizations turn. it provides a very rich, real-time medium with much of the intimacy of face-to.face communication. As Alavi and colleagues (1995) put it, “You can see the body language of the other meeting participants, and this helps make you feel more connected to them.”

No medium is perfect, of course. Olaniran (2009) interviewed employees at a large governmental organization. While 88 percent thought videoconferencing was more “convenient” than travel, 85 percent had problems dialing, 71 percent believed that videoconferencing attendees sometimes “lurked” rather than participated, and others worried that videoconferencing would completely replace travel.

Still other workers view videoconferencing as a way for their bosses to track their participation. Indeed, some workers do clam up and participate less, whether due to shyness in large group meetings (Boutte & Jones, 1996) or, according to Nandhakumar and Baskerville (2006), due to senior-level managers exerting their authority in a way that makes it hard for subordinates to participate or contradict senior-level managers’ ideas. This can be counteracted. one way, according to Yoo and Alavi (2001), is for participants to have a rapport based on a pre-existing history of teamwork.

It should be pointed out that existing studies are based mostly around room-based videoconferencing environments, not newer PC or mobile video chats. as videoconferencing moves from the performance art of the boardroom to the intimacy of one-on-one conversations, it’s unclear whether these same issues will apply.

3-D immersive Environments

In a 3-D immersive environment, a computer generates a space in which participants can interact through the use of an avatar, or virtual representation of oneself. This mimics face-to-face communication (Montoya, Massey & Lockwood, 2011) by enabling non-verbal cues like direction of gaze and gestures (More, Ducheneaut & Nickell, 2007).

Others like Reeves, Malone, and O’Driscoll (2008) found that immersive online games may promote collaboration and communication, as well as make work more dynamic and engaging, and collaboration more effective. 3-D immersive environments may also motivate and interest users more, as well as produce a deeper understanding of subject matter (Jonassen, 2004).

3-D environments seem to help high-performing teams most, because they are adept at using the environments to read each others’ non-verbal cues and gestures (Montoya et al., 2011). they also encourage equal participation in teams, especially high-performing ones. Avatars aren’t able to “free ride,” just as workers in small teams can’t loaf off in real life.

How would this work for Zestion? Theresa, who is shy and doesn’t want to be on video, might feel more comfortable as an avatar. Theodore, who is recovering from his cold, can participate from home and not be concerned about the appearance of his red nose. The power differential with Sophia being present might also be decreased. There are some hurdles: training, Sophia’s fear of new technology, and Juan’s insufficiently powerful PC. While these problems can be overcome, they do pose significant issues for managers.

The Future

By 2009, computer-mediated communication accounted for 30 to 50 percent of employee interactions (Johnson, Bettenhausen & Gibbons, 2009). Face-to-face interaction is already in the minority for many organizations and employees, and may already be in the minority overall today.

In addition to the technologies discussed above, there are other emerging tools. take social networking. While Facebook can hurt worker productivity (Nucleus Research, 2009), it–along with the business-focused Linkedin– offers huge potential for business collaboration. similarly, mobile collaboration and video offers the convenience of rich, synchronous collaboration anytime, anywhere.

As collaboration continues to go global, organizations will increasingly seek new technologies to ensure that their employees can effectively and efficiently communicate across time and distance. While it may be impossible to predict exactly which technology organizations will embrace, it is likely that the trend toward a richer, more synchronous communication medium will continue. Will email and IM fade away into obscurity anytime soon? Probably not. But should organizations continue to rely on text-based, asynchronous communication when research overwhelmingly indicates that there are better options? Clearly, there are better ways to communicate and collaborate if organizations are willing to evolve and adapt, and it is likely that successful organizations will do so.