Conversion Rate Optimization (CRO) is often presented as a sure-fire way to get more sales and solve all your marketing woes.

A quick search on the topic of CRO will lead you to hundreds of case studies touting increased social shares, decreased cost per click, surging sales, and (of course) vastly superior conversion rates.

It’s little wonder, then, that CRO often comes off as a sure-fire way to build your business.

Unfortunately, “sure-fire,” it ain’t.

There are plenty of ways to misfire with CRO. In fact, only 1 in every 7 A/B tests actually produces a positive change.

Over the years, I’ve worked with a lot of businesses who’ve experienced these “fails” and I’ve noticed that although the companies vary, the fails tend to look pretty similar.

But don’t worry, this is actually good news! It means that most unsuccessful tests are due to just a few common mistakes, so if you can identify and avoid them, your chances of success will be much higher.

In fact, once they’ve fixed their testing approach, many businesses improve their conversion rates (CR) with up to 5/7 of their tests and they learn something valuable from every test.

With that in mind, let me share three of the most common CRO fails that I see and how you can avoid them.

1. The Overdose

The first testing fail looks something like this:

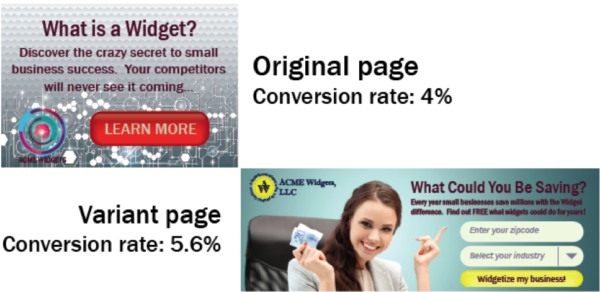

A company tests two landing pages and the variant brings in 40% more conversions…that’s awesome, right?

So why am I calling the test a fail?

Sure, technically, the test improved the company’s conversion rate, but they didn’t really learn anything from their test besides the fact that people respond differently to a different page.

“But…but…” you might protest, “The business learned that the new page is way better!”

But why is it so much better?

Imagine that you had a chronically upset stomach and thought you might have a food allergy.

If you went off dairy, gluten, nuts, soy and eggs all at the same time, your tummy might feel better. But, you’d still have no idea what you were allergic to.

In the same way, this company overdosed on changes.

They changed so many parts of their landing page (headline, reinforcing statements, call to action, hero shot, reinforcing statements, button color, etc.) that there’s no way to tell which change(s) got more visitors to convert!

On the flip side of the equation, if the variant page had performed poorly, there’d be no way to tell which change didn’t work and—like the proverbial baby in the bathwater—some great changes might have been thrown out with the rest of the “failed” page.

This can be a surprisingly easy trap to fall into.

Many marketers begin designing an A/B test with the pure intentions of, say, trying out a new call-to-action (CTA). But once they start changing things it’s hard to stop.

A little tinkering happens with the hero shot…and then they remember the new button color they wanted to try…and then…

By the time the test rolls out, the marketer might still think he or she is testing the CTA, but there are so many changes in place that it’s impossible to know what caused an increase or decrease in CR.

How to Avoid the Overdose

In order to avoid this common fail, you need clear testing goals and a strategy for achieving them.

Imagine, for example, that this company had already figured out that a new logo and a human hero shot produce more conversions and is using the page below.

Now they set a new goal to optimize the headline.

They test several possible headlines with appropriate subheaders and find that “What Could You be Saving?” has the highest conversion rate.

As a result, the company comes up with a hypothesis: “Our target audience cares more about saving money than learning something new.”

This hypothesis guides them to their next test, where they add the word “FREE” to their subheading:

If their CR goes up again, they can probably assume that their hypothesis is valid and that their market resonates with a message of frugality.

This is very valuable information that can help the company in their future tests.

For example, if their new goal is to optimize the hero shot, they might try a picture that communicates the idea that converting will save their potential customers money.

Wait just a minute, you might be thinking, Now we’re back to the landing page variant that delivered 40% more conversions in the original test. We ended up in the same place!

It’s true, a methodical approach to testing might take several more tests to produce the same results you could get with a single test, but by the time you get to the “optimized” design, you know exactly why it converts more of your traffic.

And, if you understand why a particular approach works, you can use what you know to come up with new hypotheses and tests that will further improve your conversion rate.

With an organized CRO strategy like this one, each successful test teaches you how to be more successful with your future tests.

The Exceptions

All that being said, there are a few situations where overdose-style testing can actually be beneficial.

Large site changes tend to produce large conversion rate changes, both positive and negative. For well-established companies, the risks of a colossal failure outweigh the potential benefits of a big success, so it’s often not worth it to go big.

However, if your site is in a position where “things can only go up from here,” the rewards may be worth the risk.

Another valid reason to OD on page changes is if your site doesn’t get very many conversions per day.

High-quality testing can take a while. For most tests, you usually need a lot of conversions (300-400 per variant) before you can declare a winner. If it takes you months to get this much traffic, you may not have time to test granular site changes.

In these situations, your company may benefit from trying a big change.

Regardless of the approach you use, however, you should be as organized and focused as possible. Always document the results of every test. That way, you can use what you learn from each test to guide the next experiment.

2. The Quitter

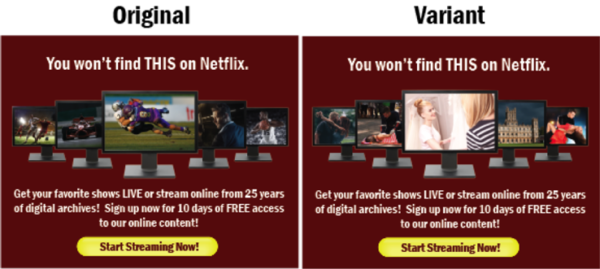

To illustrate the next type of “fail,” let’s imagine a cable TV company that wants to refine their landing page.

They wonder whether they will get more conversions from a feminine hero shot than they currently get on their more masculine page, so they put together the following test:

So far, so good. The goal is clear and the variants are focused.

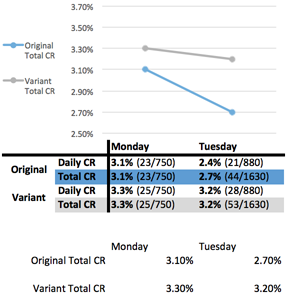

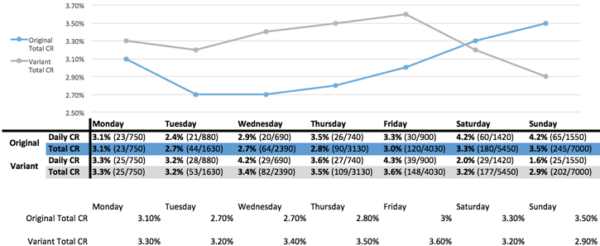

The problem arises when the test rolls out. The results look like this:

The old page has a 2.7% CR and the new one converts 3.2% of its traffic. That’s a 20% increase in conversions with the new design!

The business quickly ends the test and shifts all future clicks to the new landing page to maximize their revenue.

What’s wrong with this picture?

Well, isn’t it a little odd that the test ended after only two days? How can they really be sure that the results weren’t just a fluke?

Statistical Significance

There’s actually a statistical test you can use to see how likely it is that your test results are due to chance. It’s called a “T-test” and produces something called a “ρ-value.”

I know, I know, the words “T-test” and “ρ-value” probably send chills down your spine and dredge up dark, suppressed memories of college statistics, but stick with me, this is important.

Your “ρ-value” tells you what the chances are that your test results aren’t a random fluke.

So, if your ρ-value is .70, then there’s a 70% chance that the differences you saw in your test sample will hold true for the rest of your customers.

To be sure that they only make effective site changes, a lot of companies choose to only implement changes with a ρ-value of 0.95 (95% confidence) or more.

In this case, there’s only a 1 in 20 chance that the results were a coincidence.

However, for our cable TV company, the ρ-value after 2 days is 0.82, so there’s a 1 in 5 chance that their apparent 20% CR increase is totally bogus.

Now, in Russian Roulette, there’s a 1 in 6 chance that there’s a bullet in the chamber. Would you take worse odds than that with your business?

Fortunately, CRO doesn’t have to be Russian Roulette.

Without going too deep into where ρ-values come from (there are online calculators for that), let’s just say that ρ-values rise when there’s a bigger difference between groups and when there’s more data to support the difference.

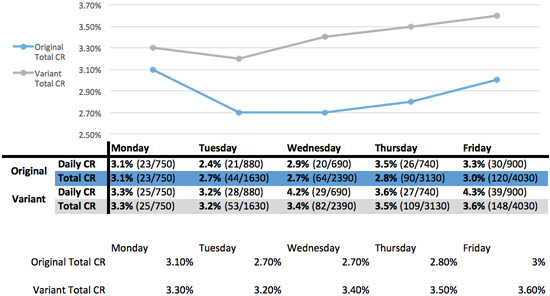

More data shouldn’t be too hard to get if the company just runs the test through the end of the work week instead of quitting on Tuesday:

At this point there’s enough data to get the ρ-value up to 0.96, so there’s only a 1 in 25 chance that the results are due to random chance.

With a ρ-value above 0.95, many people feel comfortable declaring their test “statistically significant” and implementing site changes.

The Seven Day Rule

Now, I said “many people feel comfortable” declaring a …NOT “I feel comfortable” with it.

Even though the test results are statistically significant, 5 days is still isn’t long enough to declare a winner.

Think about it like this: Usain Bolt doesn’t win in the first 50 meters, he wins in the last 10.

The same thing can happen with marketing.

If the cable company in our example continues its test for a couple more days, it might discover that although the new feminine page resonates well with the weekday audience, the company sells a lot more subscriptions on the weekend and those customers prefer the original masculine design.

By Sunday night, the test results have reversed themselves and we’re now 98% certain that the original page produces 21% more conversions than the variant.

But, if the company had stopped short with its test and funneled all future traffic to the weekday winner, they could have ended up losing out in the long run.

This is why you typically shouldn’t end an A/B test until it has run for at least 7 days. Sometimes, your test may need to run for even longer before you can confidently declare a winner, especially if your business sells a seasonal product or service.

The Exceptions

As with the Overdose fail, there are some rare exceptions to the rules I’ve just laid out.

Although tests should never be shorter than a week, there are cases where they can start to get toolong.

As I said earlier, more data allows you to extra confident about your results. However, if you only get a few site visitors each day, it might take you months to amass enough data for 95% confidence.

If your traffic is so slow that you can’t run more than a single test every month or two, you might need to consider lowering your standards.

For example, if you felt that a 1/5 chance of failure was better than not testing at all, you could choose to implement changes that get a ρ-value of 80% or better .

Additionally, you might choose to change your testing strategy if you are trying out a risky page variant.

If you’re utilizing the Overdose testing method, for instance, you may prefer not to direct a large amount of traffic to your test. Therefore, you might allocate only 25-35% of your traffic to your variant, or you might terminate a test early if your variant is drastically reducing your conversion volume.

How much confidence you need to end a test, how much traffic you give each variant and how long you run things will depend on your individual circumstances, but the general rule will always be: the earlier you end a test, the less accurate your results will be.

3. The Sideshow

The final testing fail can be hard to identify. Some tests are designed and executed superbly, but never seem to produce meaningful improvements to CR.

This can be a frustrating situation.

If you’ve run into this kind of problem with your own testing, your site might be a sideshow to your real problem—you need to fix your traffic.

For example, at Disruptive, we’ve audited over 2,000 AdWords accounts and discovered that most paid search accounts are bidding on the wrong keywords. As a result, most of their clicks come from people who really aren’t interested in converting.

These visitors are useless, expensive and unfortunately account for about 72% of the average site’s traffic.

Unfortunately, if you’re A/B testing the wrong traffic, you often end up in the same boat as the hungry chick in P.D. Eastman’s children’s classic—you get a lot of answers, but none of them are useful.

Thankfully, it can be surprisingly easy to weed out your meaningless traffic. And, as you boil your traffic down to the clicks that matter, you’ll get a much better feel for what your site’s real CR is.

By cleaning up your traffic, you’ll be able to tell how your site is actually performing and gain clearer insight into how teh variants in your tests are affecting your CR.

The Exceptions

It’s almost always a good idea to optimize your traffic before you start testing. The only real reason to focus on your website before you start cleaning up your traffic is if your current website is so unbelievably horrid that you need a change now!

But, since most of us don’t fall into that category, if you haven’t closely examined your traffic quality lately, now might be a good time to start.

Conclusion

When you get right down to it, most CRO fails fall into one of three categories: 1) you’re overdosing on changes, 2) you’re calling your tests too early or 3) your website is just a sideshow to your real problem—your traffic.

In a nutshell, effective CRO:

- Is goal driven

- Teaches you something with every test

- Follows a logical strategy

- Is well documented

- Generates meaningful data

- Tests the right traffic

If this list doesn’t describe your current CRO efforts, you run the risk of having more “fails” than successes. But, if you can figure out where you are making mistakes, you can turn your testing around very quickly.

You’ve heard my two cents, now I want to hear yours.

Do you agree with the points in this article? Are there additional CRO fails you’d add to this list? How do you minimize the risk of failing at CRO?