Recent days have not been kind to Google. Third-quarter revenues missed The Street’s expectations (and were leaked early), concerns have been voiced about the health of CEO Larry Page, and now the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) looks like they might finally bring an anti-trust suit against the search giant for illegally using the company’s search dominance to harm its rivals. While some of these negatives are overblown (like the revenue scare-Google’s 2012 third-quarter revenues increased 45% year-on-year to $14 billion. Its main revenue issue hinges on how to properly monetizing mobile ads, an industry-wide bugbear {think Facebook}), others are significant (recall Microsoft’s bloody battle in the late 1990s with the Justice Dept over its supposed web browser dominance). Regardless, even though its balance sheet may not show it (yet), Google remains the dominant power in tech.

Google’s rapid and seemingly-endless rise to power begs some fundamental questions about the future of the tech industry, and in a larger sense, of humanity. As the standard bearer (by way of sheer size and influence) of the emerging “open source” business model, is Google the personification of the future of tech, and therefore an exemplar of human evolution, or evidence of the dangers of tech over-reach, and as such further affirmation of our flawed makeup?

Put another way, by giving a nod to Google’s current practices and letting the company continue to amass money, power, and market share unchecked, are we catalyzing human excellence, or merely creating a monster? Furthermore, given that Google’s success and influence are ultimately derived from our use of its products and services, what does this say about us?

OPEN SOURCE VS PROPRIETARY

Let’s take a step back and clarify terms. While initially meant as a differentiator for software operating systems, open source and proprietary have grown to be emblematic terms of two differing philosophies among tech companies and tech-industry power players. In this context, when I say open source, think Mozilla, Facebook, and yes, Google; when I say proprietary, think Apple, Oracle, and Microsoft.

Traditionally the domain of hackers, crackpots and start-ups, open source has finally hit the big time. Its philosophy is simple: more heads are better than one. Open source takes the social, collective attitude to software development that if you open up software to all developers worldwide, it will be improved and build upon more quickly than if you close it off to the confines of one company, no matter how talented its personnel.

For all you free enterprisers out there, while at first glance this approach may sound downright socialist in nature, it is actually quite the opposite- I would argue that open source is the very personification of free enterprise and competition. Open source says, “feel free to tinker with my code (product) and make it better by adding to or modifying it;” the tacit assumption is that because competition is inevitable, it’s better to encourage sharing than stealing.

The proprietary model is the one we are more familiar with. It is a closed model often requiring a license to use. Proprietary models block external innovation except by direct competition. The proprietary model says,“ hey, this is my product. I’m not going to share its secrets with you. If you think you can improve upon it, go ahead and try, but not with my help.” This model tries to protect corporate secrets, but in so doing often encourages stealing and gives rise to lawsuits.

GOOGLE AS OPEN SOURCE POWER PLAYER

Back to Google. I can think of no company that has more-deftly profited from the open source movement. Google’s unique path of power and dominance through open source defies traditional classification and leaves many (myself included) questioning its motives. Depending on the day and the specific initiative, Google can be variously regarded as weepy-eyed idealist or cold-hearted monopolist; tech-industry white knight, or purse-snatching pirate.

So where does that leave us? By judging whether or not to trust Google’s power-through-open-source vision of the future, we are ultimately judging ourselves. In so doing, we are questioning two notions: the first has to do with whether we are truly able to appeal to the better angels of our nature, as Lincoln proposed; the second ponders whether foolish consistency is indeed the hobgoblin of little minds, as Emerson supposed.

To some extent, where you land on this depends on whether you take a Lockean view of human progress or a Hobbesian view of human nature.

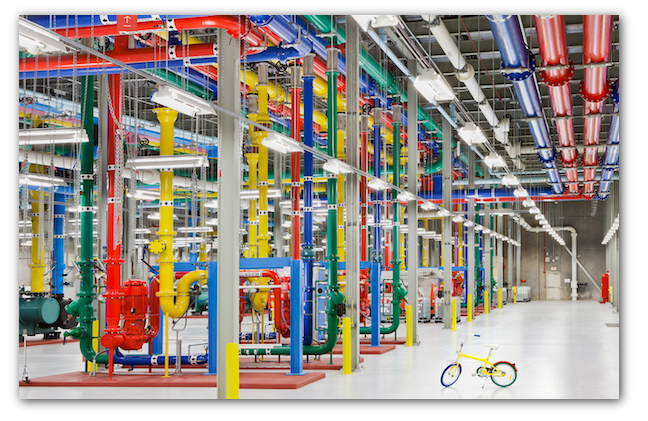

Google is clearly appealing to the former notion. This is exceedingly apparent in the latest pictorial showcase of its worldwide data centers that than can be either construed as a 1) window into the dreamy possibilities of human endeavor, or 2) rank manipulation.

Here’s an excerpt from the first page:

“When you’re on a Google website (like right now), you’re accessing one of the most powerful server networks in the known Universe. But what does that actually look like? Here’s your chance to see inside what we’re calling the physical Internet”

As you click through the pics, you are struck by two general themes: 1) Google is pretty darn powerful, 2) Their employees sure seem pretty darn happy.

The photo montage highlights these themes nicely by offsetting shots of colorful (and of course high-tech), water-cooled data centers with smiling, ice-fishing Fins. After watching, I wasn’t quite sure whether to jump up and cheer, or email the FTC and tell them to hurry up (I suppose this speaks to my inherent wishy-washiness as much as anything).

I’LL GOOGLE IT

So what’ll it be? Does Google represent the evolution of business, and by extension, of human endeavor? Can we really accumulate vast sums of power without abusing it, without engaging in over-reaching hubris (Sergei’s Google Glasses aside)?

Or is Google the wolf in sheep’s clothing, with fair appearance and foul motive? In a broader sense, are we ready for the open-source-as-power model Google presents to humanity?

The proprietary model is the more limiting, more prosaic, more “classical” approach, but it is also much safer; better deal with the devil you know, as it were. However, rejecting Google’s open-source-as-power model gives yet another tacit nod to the limitations of human imagination, vision, and largess.

At least with the proprietary arrangement, though, it’s more obvious that we’re giving away the keys to power. Moreover, it’s far easier to knock down the proprietary model as a monopoly.

Open Source, on the other hand, is muddier. Its motives are harder to gauge, its outcomes more difficult to handicap. With the open-source-as-power model we feel empowered, but we’re really not. One could say it is a more subtle, brilliant form of manipulation. Make them feel like they are contributing, make them a part, and then shape their behavior by crafting the rules to suite your expediency. That’s the Hobbesian view, anyway.

IS IT TOO LATE?

Unfortunately, the entire argument may be moot, little better than an academic exercise, as it may be too late to curb Google in any meaningful way. We’ve become so dependent on this particular “monopoly” to order our daily lives on so many levels; this is true of individuals, governments (USPTO and Defense, to name a few), and businesses alike.

Moreover, if we try to curb Google’s ambitions with anti-trust action, are we just sticking a fork into the heel of human innovation?

Either way, if left unchecked, Google will keep consolidating influence and power over innumerable industries; Google will use its semantic search data coupled with the processing power of its data centers to create the first real AI; Google will help redefine planetary resource management (no pun intended) through its asteroid mining initiatives; Google will reengineer how we get around with passenger-less cars; Google will use its search engine, its open source framework, its mobile devices, and its social influence (Google+, YouTube) to continue to shape how we do business and interact with each other, i.e. to shape how we define what it is to be human.

Is Google a Monopoly? More importantly, do we even care? Even if we take the high road and presume that Google is as good as it sometimes seems to be, are we actually prepared to live with a Google that is a forward-thinking, benevolent monopoly?

Perhaps we are, perhaps we are not. One thing is for sure: the stakes are high, higher than they may yet appear.